Research Summary and major projects

My past, present, and future research projects are united by a focus on the implications of Aboriginal Australian representations for the future of their communities, with a commitment to a sustained and collaborative research process. These include my research on the social life of Aboriginal film production and my emerging projects on Aboriginal sign language and hearing loss, as well as outer space (de)colonization. My research and writing are informed by an explicitly interdisciplinary perspective, integrating visual anthropology, Native studies, media studies, space studies, linguistic anthropology, and medical anthropology.

The research trajectory I outline below encompasses four interlinked projects that have developed through over a decade of fieldwork experiences, throughout which I have cultivated relationships with community members, organizations, and research institutes. I continue to be driven by the larger goal of facilitating collaborative research partnerships that prioritize community-defined protocols, outcomes, and analytics, while aiming to productively transform the ways in which Indigenous futures are imagined by scholars, policy makers, and broader audiences.

The Social Life of Kimberley Aboriginal Media

My book Dreaming Down the Track: Awakenings in Aboriginal Cinema, delves into Aboriginal cinema as a transformative community process. It follows the social lives of projects throughout their production cycles, from planning and editing to screening, broadcasting, and after-images. This ethnography engages the film career of Kukatja elder Mark Moora to demonstrate the impact of filmmaking on how Aboriginal futures are collectively imagined and called forth. Amid ongoing negotiations to establish the first treaties between Indigenous nations and Australian states, Dreaming Down the Track illustrates what is at stake in how Aboriginal–State relations are represented and understood, both within communities and for the broader public.

I draw on my experience working within the production teams of two Indigenous media organizations, in which I traced the biographical social lifecycles of 32 film projects over 26 months of ethnographic research in the Kimberley region of Northwestern Australia since first arriving in 2006, including 20 months of continuous fieldwork in 2014-16. The primary film that I collaborated on, Tjawa Tjawa, was screened at the Margaret Mead, imagineNATIVE, and Sydney international film festivals. I view collaborative media production as a framework for reimagining the relationship between anthropological practice, theory, and modes of representation, as well as an ethically-focused methodology.

Films emphasizing futurity are particularly critical for asserting visual and temporal sovereignty, and foster the reimagining and actualizing of what Gerald Vizenor articulates as Indigenous survivance. These films are not simply communicating visions of the future, but are actively and collectively producing them throughout the social lives of interconnected film projects spanning years. In light of the current mass defunding of Aboriginal Australian communities and organizations, understanding the production of imaginative and hopeful future-oriented media is crucial for rethinking what is possible and inevitable for people who remain so deeply associated with mythic pasts and troubled presents.

Kukatja Sign Language Filmmaking

Toward the end of my fieldwork, I was encouraged by the Indigenous media organizations to take a more central role in our collaborative film productions. Spanning several months during 2015-16 in the remote Great Sandy Desert community of Balgo, I facilitated and directed film projects featuring the local Kukatja sign language. This broader research focus traces the social life of three collaborative film productions with media workers in Balgo: (1) Marumpu Wangka, an initial short film that received unexpected circulation of over 15,000 online views; (2) a multi-camera visual dictionary of over 300 hand signs; and (3) The Hand Talk Drive-in, a half-hour nationally syndicated subtitled hand-sign drama through National Indigenous Television (NITV). The latter two, for which we received the annually-awarded NITV Spirit Award to produce, are in post-production and nearing final completion.

Hand signs are a bedrock of everyday communication and serve as a gestural lingua franca in the region. This sign language has long fulfilled a variety of communicative roles within and between communities through hundreds of regularly-exchanged signs, including gestural floating signifiers with virtually limitless potential for meaning. They are essential for silent communication while hunting and are often used to trade secrets, especially in the presence of cultural outsiders, where the contrast between the signed and spoken is a constant source of comedy and commentary on power dynamics. Hand signs also serve various cultural purposes relating to speech avoidance around stepmothers and widows, and correspond with local registers of dignified efficiency in communication.

Collaborative filmmaking provides an essential visual process for translating the complex, embodied, and humanizing intersubjective gestural practices of Aboriginal Australians. This process is also crucial for language reclamation; due to gaps in generational knowledge resulting from legacies of missionization and forced boarding schooling, many of the hundreds of signs we recorded were known only by select community elders. Building upon the foundational linguistic scholarship on gestural description and classification, this project aims to articulate the importance of filmmaking in understanding and disseminating gestural ideologies and metapragmatics in practice.

The Aboriginal Hearing Loss Epidemic

Otitis media (OM) is a common middle ear infection that afflicts approximately 709 million people each year. Aboriginal Australian youth have the highest rates worldwide, with at least 84% contracting OM, more than an order of magnitude above non-Aboriginal Australian levels. Despite being one of the most significant Aboriginal health issues, it lacks virtually any sustained research. Developing out of my current collaborative film projects on Aboriginal sign language, as well as preliminary research conducted during my dissertation fieldwork, this upcoming project seeks to intervene in the hearing loss epidemic in remote communities. In many communities, every single child contracts OM, which leads to severe hearing loss or worse in at least one-third of all children. This exacerbates lifelong cycles of structural violence; for example, the majority of Aboriginal prison inmates have significant hearing loss.

In the wake of governmental programs that have been unsuccessful in addressing this issue, collaborative interdisciplinary research is crucial. As this topic covers broad areas of expertise and articulates with complex histories of ongoing dispossession, I would engage team research encompassing community members, social scientists, medical researchers, and policy experts to help identify underlying causes and attain deeper insights centered around Aboriginal perspectives on health and wellbeing. Collaborative film productions would be integrated within the project to better understand how community members imagine this issue, as well as to provide an effective means for translating and disseminating our findings.

Furthermore, recent public health media campaigns emphasize the individual choices of hand washing, nose blowing, and eating a good diet as preventative measures, despite medical research suggesting that these strategies would have a relatively small impact on the already-existing epidemic rates of OM. Thus, tracing the social life of these media campaigns and their relationship with medical research, policy papers, and the lived everyday life of community members will be crucial in better understanding this complex issue. I aim to engage this without appealing to a politics of suffering, instead emphasizing the vitality of communities in spite of colonial legacies, as well as the importance of collectively imagining hopeful futures, in this case embodied by the children themselves.

Outer Space (de)Colonization

I have been inspired by the exciting work of outer space anthropologists, which led me to interview three leading scholars for an AnthroPod podcast trilogy. I have also found insight into this topic from my participation in the 2018 SETI Making Contact workshop and as an international advisory board member of the ETHNO-ISS project on the International Space Station.

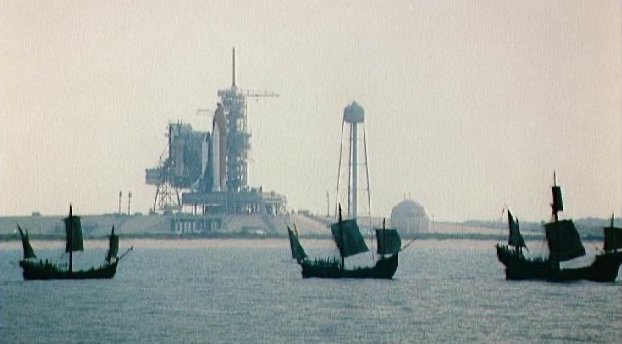

My work emphasizes the ways in which current outer space ventures serve as extensions of colonial legacies. For example, I analyze parallels between (1) SETI and James Cook’s colonial voyages to ostensibly measure the transit of Venus; (2) contemporary alien intelligence discourse and the rise of phrenology and race science in the 19th century; and (3) the similar role of nostalgia in MAGA and space privatization/militarization. I have published these topics in a diversity of genres, including the peer-reviewed journal, edited chapter, keyword article, online blog, and podcast. General audience engagement is particularly important on this topic, as broad public imaginaries of space will largely define human futures beyond Earth in the coming decades. I have also written creative fiction on the relationship between Indigenous dispossession, outer space colonization, alien invasion, and the ethnographic imagination.

Throughout, I highlight the work of Indigenous science fiction filmmakers and scholars who are creatively reimagining the nature of futurity, celestial beings, and inner/outer spaces. The current revitalization of Polynesian wayfinding and the Thirty Meter Telescope protests in Hawai’i are especially relevant. These, among many other examples, demonstrate the importance of centering not only Indigenous critiques of space imperialism, but also how Native studies scholarship is essential for collectively imagining non-colonial ways of exploring vast distances across time and space.